Despite the recent hearing on massive fraud connected with the Renewables Fuel Standard, the Senate Finance committee has approved the friendly-sounding “Family and Business Tax Cut Certainty Act of 2012.” Among other provisions, the Act would extend the $1/gallon tax credit for biodiesel producers through 2013, a measure estimated to cost $2.1 billion (in forfeited tax receipts) over 10 years. Thus, the government continues to lavish massive support—both with tax credits and outright mandates for purchase—on a sector without addressing the obvious problems in implementation. Furthermore, even if the programs were administered flawlessly by angels, the government’s encouragement of renewables is an inefficient distortion of energy markets.

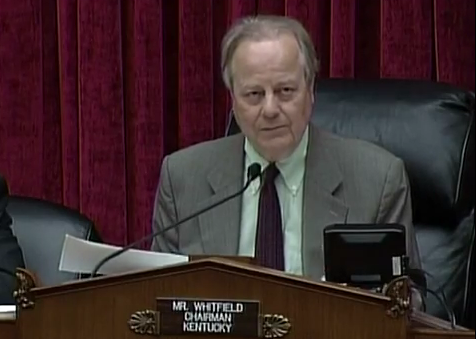

In his July 11 testimony to the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers (AFPM) President Charles Drevna explained the massive “RIN” fraud plaguing the EPA’s Renewable Fuel Standard. Here is a summary of the testimony:

[The] Renewable Fuels Stand (RFS) [requires] obligated parties to blend increasing volumes of biofuels into the transportation fuel supply. There are several nested mandates within the RFS, including a requirement for 1 billion gallons of biomass-based biodiesel. In order to demonstrate compliance with the RFS, obligated parties submit a requisite number of renewable identification numbers (RINs) to EPA by the end of February following the compliance year. RINs essentially act as credits that can be bought and sold among biofuel producers, brokers and obligated parties.

In order to facilitate RIN trading, the EPA established the EPA Moderated Transaction System (EMTS), through which all RINs must be generated. Only EPA registered biofuel producers that have submitted third party engineering reports are eligible to generate RINs on the EMTS, although other parties are then able to trade RINs, and in particular biodiesel RINs.

Unfortunately, some bad actors are taking advantage of weakness in the system and have generated and sold more than 140 million fraudulent RINs that we know of. For context, 140 million RINs constitute between 5-12% of the biodiesel RIN market to date. [Bold added.]

Drevna went on to criticize the EPA’s handling of the scandal, taking more than a year to warn buyers when red flags were raised about certain issuers of RINs. Thus, innocent firms unknowingly bought fraudulent RINs from groups that EPA knew were suspect, and yet EPA adopted a “buyer beware” policy, whereby it was the responsibility of refiners to come up with valid RINs. In practice, this meant certain refiners had to pay double, once for the fraudulent RINs and again to obtain valid ones, in order to comply with the RFS mandate.

Drevna pointed out that, in his opinion, EPA thus far had not given much guidance to refiners as to the proper amount of “due diligence” in verifying the authenticity of RINs. Thus the actual compliance cost of the RFS mandate is higher than a naïve textbook analysis would indicate, as many firms are paying twice, not to mention the current uncertainty of dealing with the tradable RINs market at all.

Despite these problems, the Senate Finance committee recently passed a measure extending many tax advantages, including:

Incentives for biodiesel and renewable diesel. The bill extends for two years, through 2013, the $1.00 per gallon tax credit for biodiesel, as well as the small agri-biodiesel producer credit of 10 cents per gallon. The bill also extends through 2013 the $1.00 per gallon tax credit for diesel fuel created from biomass. Based on preliminary estimates, a two-year extension of this proposal is estimated to cost $2.1 billion over ten years. [Italics in original.

A $1/gallon tax credit represents a massive subsidy, given the margins in the industry. The problem is not with tax cuts per se, but with the government clearly picking winners and losers. By levying a heavy burden of tax, and then exempting special groups, the government establishes a very unlevel playing field.

Both for reasons of minimizing fraud and moving toward an efficient energy sector, the federal government’s continued support for renewable energy should be reconsidered.